Introduction

Vague complaints like “I’m having Wi-Fi issues” or “the Wi-Fi is slow today” are common in enterprise environments and often difficult to diagnose. During one of my monthly consultancy visits to a large hospital—where we had recently taken over support for the existing LAN and WLAN infrastructure—I was tasked with improving network performance and resolving persistent issues that the hospital’s IT Helpdesk could not address. These issues were not considered urgent, so they were often deferred until my scheduled visits. It is also relevant to note that a few years prior, a colleague had implemented a manual channel plan at this site due to the RRM not functioning as expected, with neighboring APs broadcasting on the same channel.

Problem

During one of my visits, a helpdesk staff member informed me of general complaints about slow Wi-Fi performance. The issue was not tied to a specific device or location, making it difficult to isolate. I asked for more details, but the staff could not provide a clear pattern or affected area. With limited information, I began monitoring graphs and logs on the WLAN controller. I discovered that many APs on the 5 GHz band exhibited unusually high channel utilization—between 70% and 80%. Since this affected more than just two or three APs, it was unlikely to be caused by localized interference. I validated the manual channel plan previously implemented by my colleague, and it was still correctly configured.

Solution

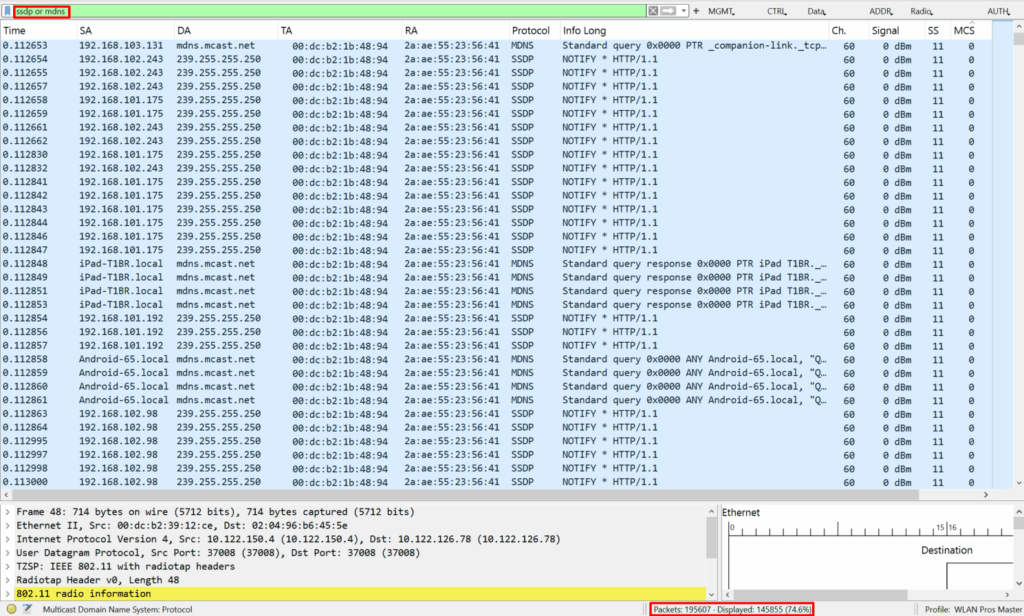

If my CWAP studies taught me one thing, it’s that packets don’t lie. With modern WLAN systems, it is relatively easy to perform a packet capture on a specific AP. I initiated a capture and quickly identified the root cause: a flood of multicast packets originating from guest and BYOD devices. These packets included SSDP “NOTIFY” and mDNS traffic.

Because the guest SSID was open and lacked a captive portal, it was accessible to anyone in the hospital. Many mobile clients, including my own smartphone, run streaming apps like YouTube, Netflix, Spotify, or IPTV services. These apps often attempt to discover nearby devices such as smart TVs, Chromecasts, and smart speakers using multicast protocols.

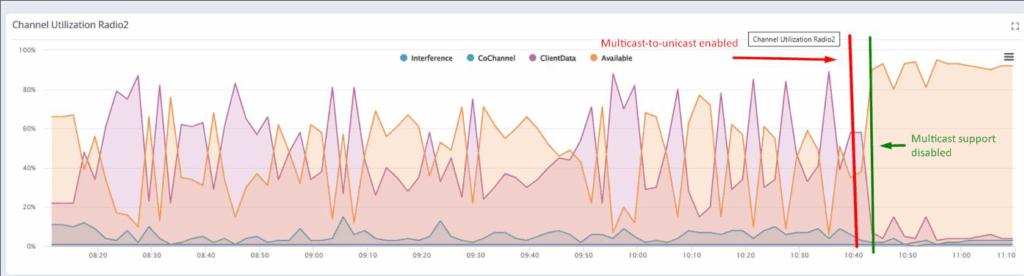

Multicast traffic is particularly problematic in WLANs because it is transmitted at the minimum base rate (MBR) to ensure all clients—regardless of distance from the AP—can receive the frames. This results in inefficient use of airtime. The first step I took was to enable multicast-to-unicast conversion. This feature allows the controller to send multicast frames as unicast packets to each client at the highest possible rate based on their SNR. While this improved airtime efficiency, the volume of traffic remained high.

Upon further investigation, I discovered that multicast bridging for SSDP (239.255.255.250) and mDNS (224.0.0.251) was enabled on the guest SSID. This is not a typical configuration unless specific business applications require multicast support. Since this setup was inherited from a previous provider, I had overlooked this setting during my initial validation. I confirmed with the customer that no multicast support was needed for the guest WLAN. It appeared the setting had been enabled for testing purposes and was never disabled.

After disabling multicast bridging on the guest SSID, I observed a significant drop in channel utilization. The visual graphs from the WLAN controller clearly showed the improvement, and user complaints about slow Wi-Fi ceased immediately.

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of monitoring and controlling multicast traffic in high-density WLAN environments. Even seemingly innocent services like device discovery can severely impact performance if left unchecked. By applying CWNP best practices and leveraging packet analysis, I was able to identify and resolve a complex issue efficiently. This experience reinforced the value of thorough validation, proactive monitoring, and understanding of the behavior of multicast traffic in wireless networks.